When I approached my co-conspirator, Cartland, about presenting at Reclaim Open to discuss the work we do in the Digital Knowledge Center (DKC) I had one request and that was not to do something too serious. In the spirit of many presentations I saw Jim Groom and Tom Woodward do (Greeting from Non-Programistan) I thought it would be fun to be a bit more performative and we decided that using the rhetoric of the “get rich quick scheme” to talk about the work we do would be a humorous framing. We created an over-simplified, if not convoluted, framework of reclaiming digital fluency through our patented “prongs of engagement” which, of course, form the Trident of Digital Fluency. Since we chose to do a 15 minute presentation there wasn’t any time afterwards for conversation, so this post is an attempt to capture the details of the presentation as well as discuss what this has to do with digital fluency.

Prong 1: Workshops

Workshops get a bad wrap (sometimes rightfully so), but it seems to be a perennial refrain that people “want workshops” (even if they never show up). So, in 2021 when one of our student workers asked if we could start doing workshops I was initially skeptical. By the end of the semester my feelings about our student led workshops started to change and I was surprised how eager some of our students were to do these and delightfully surprised at the attendance at some of them. There was certainly room for improvement though and we’ve iterated ourselves to a fairly successful model that works for us. It goes a little something like this:

- Finding workshops

- While many of the workshops are done by our student consultants we do invite others to propose their own. We have a form that anyone could fill out to request a workshop they’d like to see or to propose an idea they’d like to present on. Our goal is to give students an opportunity to share their expertise with others, so we aren’t particularly picky about what the topic is, which opens us up to all sort of cool workshops (like creating an interactive fiction game or launching your DJ career on Twitch).

- Building the workshop

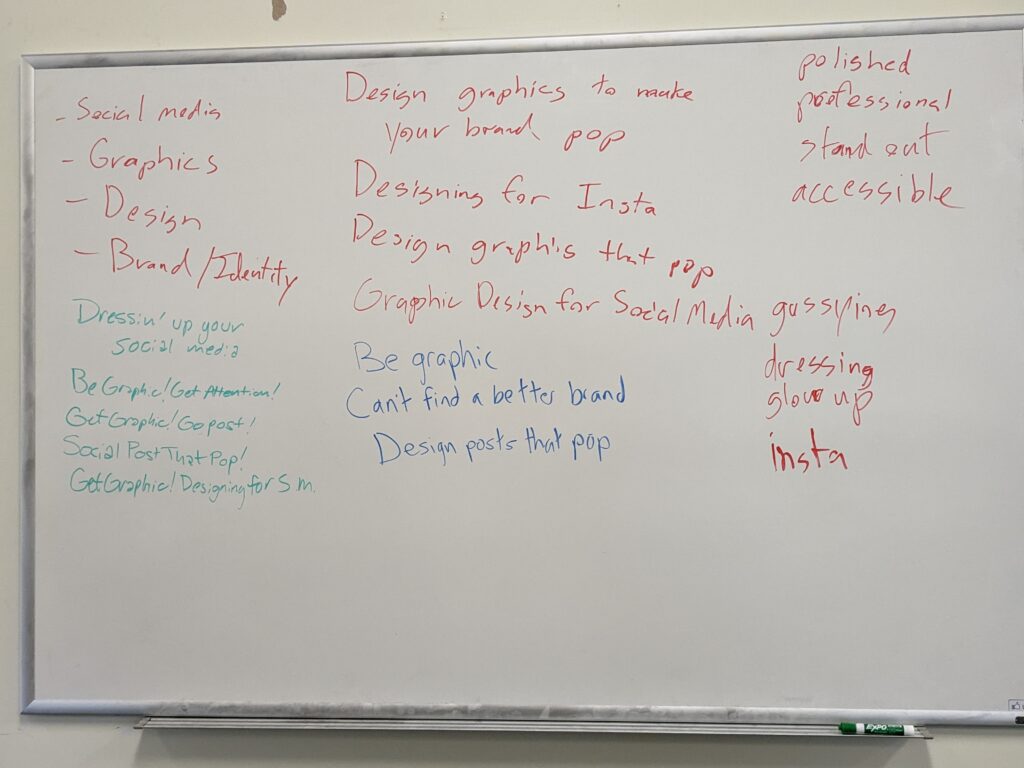

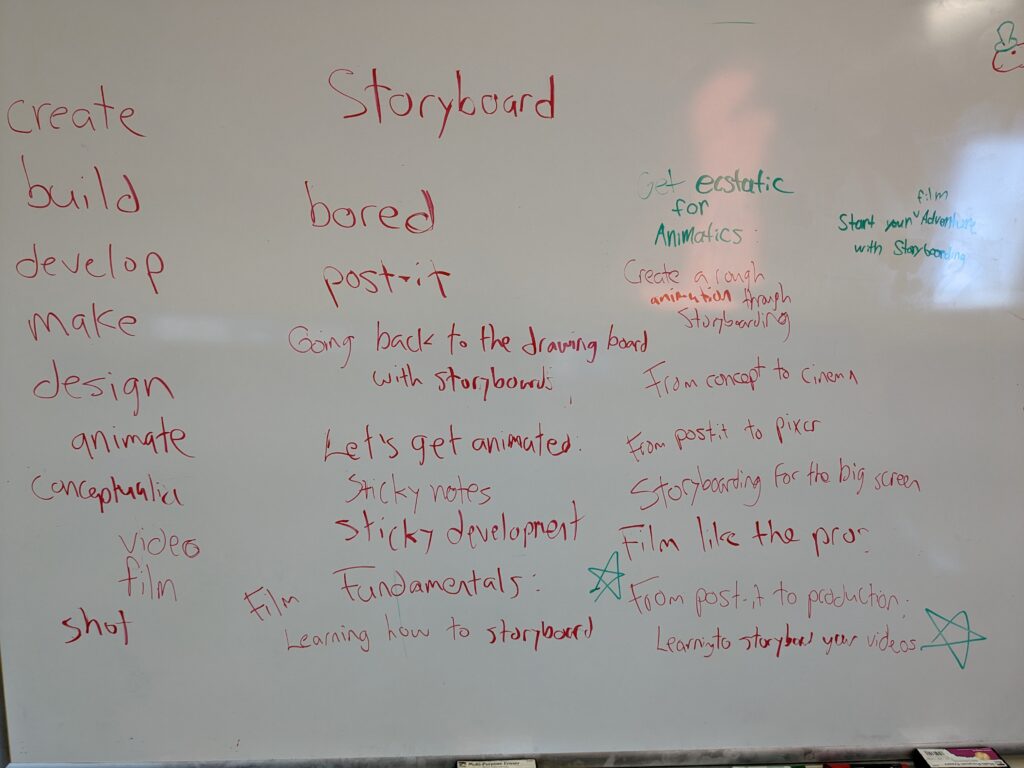

- After we get a proposal we have an initial jam with the presenter to get an idea of what the workshop will be about and help them figure out the beats of the presentation. This is where a lot of the magic happens. During the jam we engage in a back and forth with the student as we work to understand what they know and mold that into something that is accessible to a wide audience. Students rarely get the opportunity to teach others and these workshops gives them a perspective about teaching and learning they did not have before. I imagine for many students they are simultaneously thinking, “wow, I really do know a lot about this” and “teaching is not as straightforward as I thought it was”. Lastly, before we are done we come up with a snazzy title for the workshop by getting in front of a whiteboard and brainstorming together. This is one of my favorite things to do because we do not treat it too seriously (I love proposing bad pun titles) and is a rare opportunity to engage in brainstorming that feels wildly open and creative. Some of the best titles have come about riffing on what was a silly suggestion. After the title is chosen we are ready for the necessary evil that is…

- Marketing the workshop

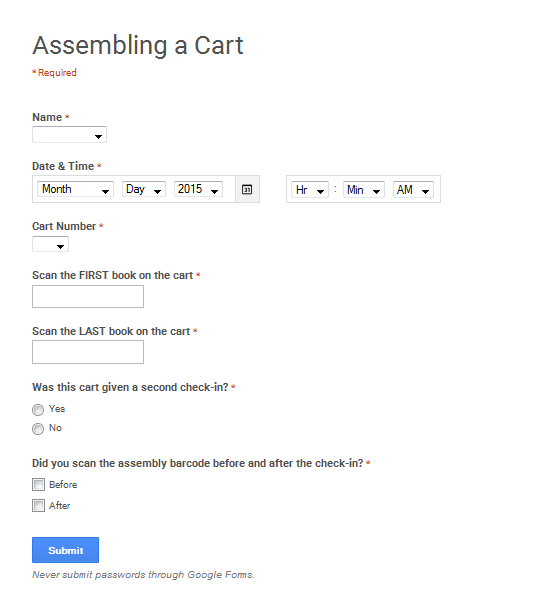

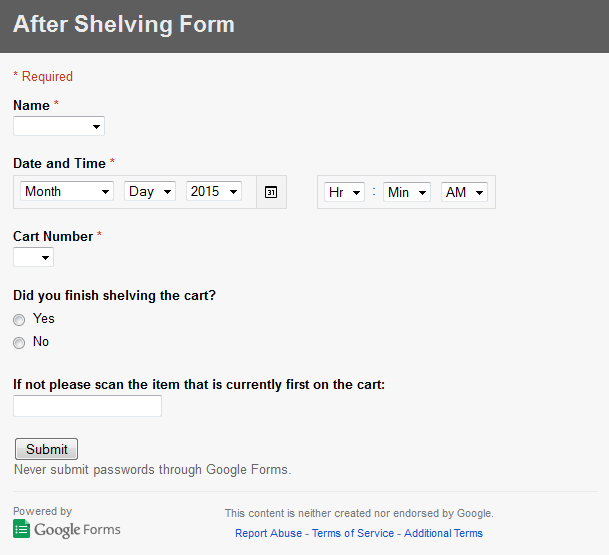

- Once the workshop wheels are in motion we set our student workers to the task of creating graphics, blurbs, an event for our events page, and of course pushing the content to all the different platforms on campus. We take the marketing piece off the presenters plate so they can focus on putting together the workshop. Cartland put a ton of effort into figuring out the process for this so that we could hand it off to our student workers. Our feedback has revealed that a lot of students attend because of our advertising efforts.

- Workshop rehearsal

- Before the actual workshop we have the presenter run through the workshop under “show conditions” (or as close to that as we can possibly get). This is where we can try out the hands on pieces and work out the technical issues that inevitably arise. It gives us time to give the presenters feedback and hopefully give them a boost of confidence before they present (and I imagine that getting in some practice on presenting may help with anxiety about running a workshop).

- Fabulous workshop!

- The day of the workshop we make sure catering is lined up (we’ve discovered our students love hot cocoa) and then at the start of the workshop we introduce the DKC, our other upcoming events, and most importantly the student who will be doing the workshop. Once it gets going it is the presenters time to shine. Many of our student workers will attend these workshops. We consider workshops a form of professional development for them (and they get paid for their time). Lastly, I’ll mention that we do pay presenters a small honorarium for all their hard work.

Prong 2: Fellowships

This is the newest of the prongs and we’ve only recently established a process (although I’m sure there is more iteration to go). Our goal with the Digital Knowledge Fellowship is to empower students to deeply engage in a specific area of digital creation and give them incentive (stipend or credit) to dedicate the time to explore something they are excited about. This idea arose of out our desire to try and encourage students to pursue a passion project more deeply by making it financially possible to achieve those projects. In return for our support of their project we get to learn from their explorations. So how do we make this happen?:

- Application

- Students can learn more and apply to the fellowship through a simple application process. Right now we’ve had to actively encourage students to apply so we haven’t had to deal with having more applicants than we can support (a bridge we will have to cross if we get there).

- Initial Meeting

- Before we get going we have an initial meeting to learn more about what the student wants to do. Since the application doesn’t require a lot of information this is our opportunity to learn more from the student and also to make sure they understand what our expectations are during the fellowship.

- Project Contract

- Once the fellowship is a go we work out the finer details. There is what the student hopes to achieve with their project and how they think they will get there. We also include what we would like in return (e.g. a workshop or a presentation on their work). Helping the student scope out the project is a key part of this. Some student are not used to having control over defining what the end goal of a project should be or what success might look like for their experiment. This contract also sets up an initial schedule of deadlines. This can be flexible, and in fact we expect it to change, but we’ve found that this bit of structure helps keep everyone on track around expectations.

- Meetings, meetings, meetings

- Throughout the semester we regularly meet with the fellow. Since we don’t have an expectation that students have to be in our space working on their fellowship this gives us a defined time to hear about their progress, if they need support, or if there are any adjustments that need to be made to the deadlines or deliverables (as you can imagine students are often more ambitious than is feasible, but that is okay!).

- Fabulous project!

- We’ve done two fellowships so far, one involving 3D design and printing to make a practice bagpipe chanter, the other involved green screen video and animation to capture dreams. I’m still working on having a place to showcase the work they’ve done, but it so gratifying to watch these projects unfold over the course of a semester.

Prong 3: Jobs

This is the prong that has been around the longest. Since it’s founding in 2014 by the inimitable Martha Burtis, the DKC has been about peer to peer support. It was an outgrowth of the work DTLT did with faculty in support of class projects and assignments. As you can imagine the more classes you work with the more students with questions. Additionally, these students also make it possible to grow and sustain additional services or programs that support the mission of the DKC. As far as the peer to peer support goes there is plenty of research showing the benefits of peer tutoring not only for those students who use the services but for the students who provide the support. I feel fortunate that Cartland and I share the same view that the students who work for the DKC aren’t just here to help us “get work done” but we are there to give them experience and skills that will help them on their next steps after college. There is nothing more rewarding than hearing that a student’s experience working in the DKC has helped them succeed after college.

Now, I’m not sure about your institution but I know at mine we’ve long underrated the amount of work it takes to give students a valuable employment experience. If you have ever managed students you quickly realize how much work it is. I won’t get into detail about what it takes to manage students (honestly that could warrant several blog posts), but I will note that we spend a whole semester training students in a cohort model before they are considered official consultants. So, what do these students do once they are working for the DKC?:

- Consultations

- This is the “flagship” service we provide. We provide support around many different digital tools and skills. Honestly, this has been one of the more difficult things to figure out, how do you make it clear what you support and connect students to the supports they are looking for.

- Class visits

- We’ve invested more in class visits over the last year. In some ways these visits are less about the practical help in the moment and more about putting ourselves in front of the students. There have been many times a student has intentionally booked an appointment with a student worker because they knew them from a class visit. I’ll also mention that like workshops, we have found that our class visits are more successful when we can collaborate with our student workers on the presentation for the class.

- Writing and updating guides

- During the early COVID days we were looking for ways to keep our students busy but also have them work on something that could be useful. From that grew our series of guides on tools and how to get started on projects. These have become invaluable for class visits and training new students.

- Lead on services and other things that help use get the work of the DKC done. This upcoming year we are moving away from the model of having one or two “supervisors” and more towards having many “lead” positions so that student workers can really dedicate time at become expert at those positions. For example:

- Marketing Lead

- Is tasked with making sure we are getting the word out about all our events and services and works with other students to make that happen

- Workshop Lead

- This student coordinates meetings with presenter, jams on the workshop, and relays to the marketing lead information about the event

- Marketing Lead

- Projects

- During downtime we expect that our consultants are working on things to professionally develop. We’ve found one of the more effective ways to do this is to define a project that is meaningful to them and bonus if it means we are getting something we can use. Many videos and graphics that we use have come out of these learning projects.

So, digital fluency?

At the conclusion of our presentation we had a series of questions that brought home the reality that the approach we are taking is hard to scale, requires time (and a lot of it), investment in people, and it can be hard to measure impact. But despite all this (or more factually because of this) the students who come into contact with our “prongs of engagement” are having meaningful educational experiences.

“So, what does this have to do with digital fluency?”

Glad you asked because honestly the answer is nothing and everything. The framework that we showed could easily apply to many different kinds of “fluency” or educational outcomes because it isn’t about the “bits”, like how to use technology and interrogate it (although this is very important and I do get paid in part to know these things), but how do you engage students about the bits in a meaningful way in the first place? If you look at what we proposed (workshops, fellowships, jobs) there isn’t anything radically new there, but what we do emphasize is the importance of human connection in those three prongs. We don’t just do workshops, we co-build a workshop with a student and along the way we have conversations around accessibility, ethical uses of tools, how to explain to others what you know. We don’t want to have student who just work for us, we want to have students that will care about helping the individual in front of them, that want to expand their ability to tackle technology questions both practical and abstract, and to build their creative confidence with digital tools.

One of the reasons we titled our presentation “Reclaiming Digital Fluency”, was to resist the narrow track conversations around digital fluency can sometimes go down (learning outcomes, badges, etc) in favor of the broader scope of what it means to educate a student. Perhaps this happens more in the technology field where there is a lot of focus around “skilling” people around digital tools that can lead to conflating digital fluency with digital technology proficiencies. As if digital fluency were merely a series of activities strung together where you end up with a badge at the end. Education is relational, not transactional, but how does one capture that in a meaningful way? How do I even know students are becoming “digitally fluent”? (As an aside: imagining that my interactions with students must lead to some sort of measurable outcome is nausea inducing. What if the time we spend with that student on a workshop ends up being useful for them for some other reason? Is that not worth something?).

To the “capturing piece” I will say that one thing we’ve identified we need to do more of is build in the reflection piece with students. As facilitators to students learning we often see the growth and change that they are unable to see in themselves. Even more alarmingly students sometimes believe the work they do outside of class (especially if it is fun) doesn’t “count” as part of their education. It is incumbent upon us to have these conversations with students to reflect back to them what we are seeing, to give them words to explain what they’ve accomplished, and to encourage them to cogitate on their own experiences. We need to help them see it at all matters and that, as Dewey put it, “Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.”